Drill, baby drill!

In addition to being Donald Trump’s energy mantra, it’s also the basic description of a junior mining company’s job.

Drill… then map… then drill some more.

We’ve spent some of our digital real estate here illuminating the fundamentals of what is a pretty science-heavy (and usually difficult to understand) industry. So that when you, as a mining investor, read about a company’s activities, you have a firmer grasp on what it all means.

Today we want to explain a few basics of what goes into a junior mining company’s drill program…

Starting at the End

The end goal of all a junior miner’s drilling is to be able to map out a proven mineral reserve.

To get there, however, a prospective reserve has to go through a few iterations…

Before a junior can even start talking about reserves, they have to prove that a mineral resource exists in the first place. Strictly speaking, a “resource” is “a concentration of minerals that has a reasonable prospect of economic extraction.” In other words, it’s a deposit that could potentially be profitably mined.

Resources are broken down into three categories: Inferred, Indicated, and Measured.

An inferred resource has a low level of confidence when it comes to mineability. It basically tells you that there’s ore present in the ground.

Indicated resources come with a little more confidence. They are determined after a number of drill holes have been assessed. This is the point where a junior can start making some educated guesses about the economic viability of mining.

A measured resource has the highest confidence about the grade, quantity, shape and density of a deposit. This is the point where a miner can start doing actual feasibility studies on the deposit. (Feasibility studies include all the costs for building the mine, quantities that are mineable at various ore prices and so on.)

Once those studies get underway, then your resource gets transformed into a reserve. And there are two categories here: Probable and Proven.

A reserve is probable when feasibility studies indicate extraction CAN BE justified economically. A reserve is proven when extraction IS economically justified.

Getting to that end goal of proven reserve all depends on your drilling program.

Drilling Directions

Once a drilling program gets underway, there are basically two directions a miner can go… in or out. And each direction is aimed at a different result.

Let’s back up one second.

Once a miner has completed early stage exploration via soil sampling and geophysics, they’ll determine where to start drilling. Then, based upon those results combined with their original data, they’ll determine where they want to sink subsequent drill holes.

Hopefully, the shape of an ore deposit eventually starts to develop.

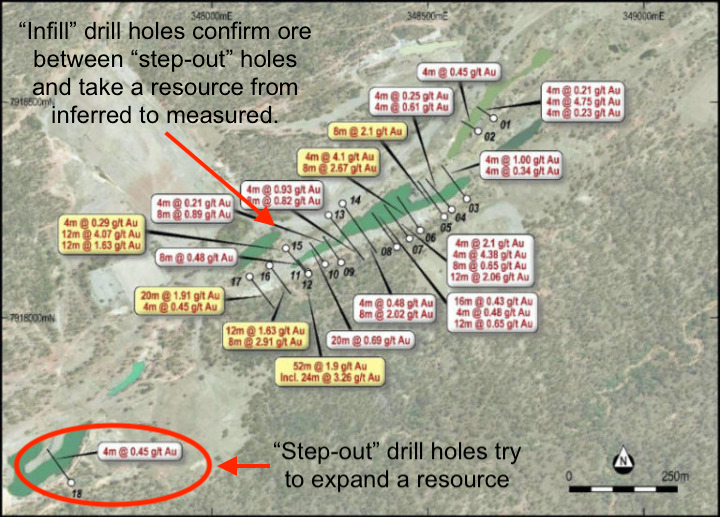

As it does, a miner will either drill “infill” holes — holes between holes that have already been drilled — designed to add more certainty to the deposit size, or they’ll drill “step-out” holes that look to expand the overall size of the resource.

If a step-out hole returns promising results, they’ll start drilling infill holes to map the expanded area of ore.

The Tools for the Job

When it comes to the actual work of drilling, there are a number of ways a miner can bore into the ground. The choice of drill rig usually depends on a number of factors like the type of material they’re drilling into as well as the stage of exploration they’re in, not to mention their drilling budget.

There are two methods of drilling you’ll likely come across when reading about miners’ progress: Reverse Circulation and Diamond Core drilling.

Reverse circulation (RC) is a more cost effective (cheaper) means of sampling a potential deposit.

RC drilling is a “concussive” process where the drill head spins and rapidly impacts the ground. Tungsten-carbide drill heads effectively pulverise the rock which is then blown back up through a hollow drill rod with compressed air.

The “cuttings” are then bagged and labeled indicating at what depth they were discovered.

This method of drilling is really only viable to about 600 meters and, as it results in bags of rock chips, tends to be used in more early exploratory drilling.

Diamond core drilling on the other hand, uses a diamond-impregnated drill bit that cuts through the rock and produces a solid, continuous core sample.

Source:

These result in significantly higher quality samples — plus they can drill up to 3,000 meters deep.

Of course all that comes at a cost. Diamond core drilling is significantly more costly than RC drilling.

Drilling programs can be complex endeavors — combining science with some sophisticated sleuthing — gathering the evidence they need to map a mineral reserve.

And now you have a little better understanding of the process…